This semester, I ventured into terra incognita. Worlds unknown and becoming known. I dabbled with magic systems, mingled with strange races, and wielded sharp blades. In short, I taught my first course on writing the speculative fiction novel. Tonight, it came, with the semester, to a bitter sweet end. These students wrote their hearts out this semester, spilling them drop by drop onto the page in the best of all possible ways. They wrote with the passion of the faithful. (There was a curious lack of dragons, but we'll let that pass.)

I've loved teaching this class, which is interesting given its history. The course has never been offered before because, though the department knew there was student interest, no faculty member particularly wanted to read multiple chapters from early drafts of speculative novels. That's just not their bag, baby. And I understand their position. I, too, am a fan of literary fiction. It's what I write and it's what I read, but I think there's something to be said for teaching speculative fiction. So I'm going to say it.

A quick list, as it were, of just a few things writing spec fiction brings out of the students:

1) Passion. The students who took this class were a self-selected group. Many have been working on spec fiction novels from their early teens. These writers were absolutely committed to the job of writing, and dedicated to finding the awesome in their stories. Their passion rejuvenated mine as well, reminding me that, after all, finding the awesome in any story *is* what it's all about.

2) Knowledge. When I teach a standard literary fiction writing class, part of my job is to educate the students about the writing that's out there. Most of the literary writing students know is dated (Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Hemingway), and I have to bring them up to speed with recent trends--something that's difficult to do in a semester when I'm also trying to teach basic writing craft and workshop their stories. In this class, however, the knowledge of the literature was reversed. They know contemporary spec fiction far better than I, so I could teach them about craft while they helped educate me and each other about the current trends in the field. I did a ton of reading to prep for this class, but the students had years of lead time to out-read me. It created a great collaborative dynamic, allowing them to really apply what they knew to the writing they were doing.

3) Willingness to be challenged. I started this class with the premise that, if they were still working on Dragonlance-style fantasy hoping that it would be good enough, they were wrong. (And yes, there were some writers who thought exactly this.) We talked at least about how the field was shifting, how electronic markets and intense competition was driving the quality of writing and invention up, and how they were going to have to be better than they imagined possible to compete. Because they had the passion and the knowledge I mentioned, they drove each other and challenged themselves to levels of extraordinary growth.

4) Invention. Every fiction writer invents, but those working in spec fiction bare a burden of world building that I am happy to forego. The critical thinking these students did about everything (from ecosystems to governments to the cost of magic to space travel) was humbling. I often wished my peers in other departments (Biology, Economics, Physics, etc) could have been there to hear the application of so much college learning to fictional worlds. Fiction allowed these students them a place to put all their learning into action in a way that was truly exciting to behold.

I'm going to miss these kids. And so, here's a dragon heart for them, one that I hope will continue to breathe fire into them as they breathed their infectious passion into all they did this term.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Sunday, April 8, 2012

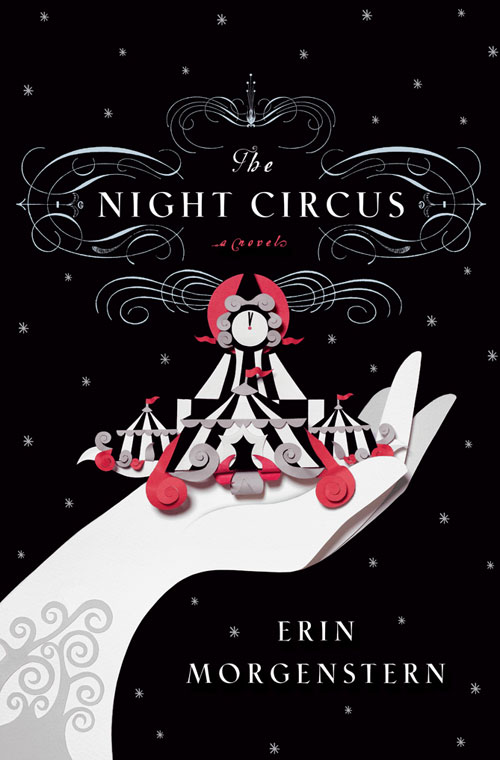

The Night Circus

Recently, The New York Times published "Your Brain on Fiction," an article that examined the neuroscience of reading imaginative literature, reporting that reading about smells and actions stimulates the brain in the same way that living those experiences does. In short, our brains treat the fiction as reality, showing that our long-standing metaphor of fiction bringing new worlds to life is, in terms of brain function, a literal as well as figurative truth. The article ends with the following lines: "Reading great literature, it has long been averred, enlarges and improves us as human beings. Brain science shows this claim is truer than we imagined."

A friend of mine forwarded The New York Times article to me as I was reading Erin Morgenstern's debut novel The Night Circus, and if there was ever an invented world you might be glad to descend into and live in a while, this is it. Morgenstern's novel is rich in precisely the kind of detail most likely to stimulate our minds: the dark caramel of a coated apple, the scent of popcorn on a clear night. Her novel imagines for us a circus more amazing than the most wonderful we've been to and brings the place to life through rich images that leave our mouths watering.

I've heard that the seeds for this novel began not with character or plot but with setting, the circus itself, and I believe it. Morgenstern peppers the novel with brief second person chapters that invite us in to new tents and passage ways. These moments reminded me strongly of Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities both in their image-driven beauty and their poetic language. (OK, maybe not quite so poetic as Calvino, but that would be setting the bar impossibly high, would it not? But they are rich and beautiful and finely wrought.)

What grounds the novel is the plot and characters that Morgenstern applied once she had created this amazing circus. Whereas Calvino's prose poetry collection is very loosely "plotted" with the story of Marco Polo explaining the places he's been to Kublai Khan, The Night Circus is more firmly grounded in a magicians' battle. Two children have been bound against their wills to compete for magical supremacy and the circus is their venue, the place where they test their skills against one another by creating ever more fantastical tents.

The result is a high interest page-turner with a literary quality, a novel that those who love fantasy and those who love language can enjoy equally.

A friend of mine forwarded The New York Times article to me as I was reading Erin Morgenstern's debut novel The Night Circus, and if there was ever an invented world you might be glad to descend into and live in a while, this is it. Morgenstern's novel is rich in precisely the kind of detail most likely to stimulate our minds: the dark caramel of a coated apple, the scent of popcorn on a clear night. Her novel imagines for us a circus more amazing than the most wonderful we've been to and brings the place to life through rich images that leave our mouths watering.

I've heard that the seeds for this novel began not with character or plot but with setting, the circus itself, and I believe it. Morgenstern peppers the novel with brief second person chapters that invite us in to new tents and passage ways. These moments reminded me strongly of Italo Calvino's Invisible Cities both in their image-driven beauty and their poetic language. (OK, maybe not quite so poetic as Calvino, but that would be setting the bar impossibly high, would it not? But they are rich and beautiful and finely wrought.)

What grounds the novel is the plot and characters that Morgenstern applied once she had created this amazing circus. Whereas Calvino's prose poetry collection is very loosely "plotted" with the story of Marco Polo explaining the places he's been to Kublai Khan, The Night Circus is more firmly grounded in a magicians' battle. Two children have been bound against their wills to compete for magical supremacy and the circus is their venue, the place where they test their skills against one another by creating ever more fantastical tents.

The result is a high interest page-turner with a literary quality, a novel that those who love fantasy and those who love language can enjoy equally.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)